December 2024

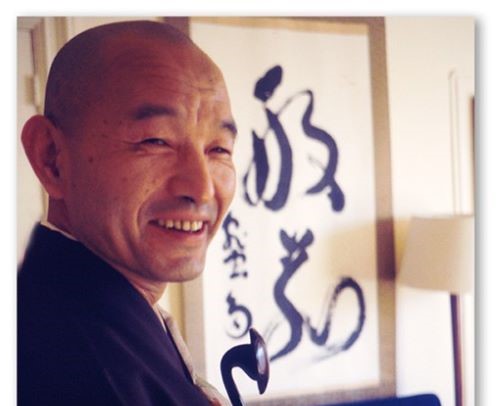

Tis the season of dana, a time not only of giving but also of receiving. Indeed, how we receive something is often as important as how it is given—as Maezumi hints, the act of receiving is itself a kind of gift.

I love the idea that anything—everything—can be a gift—and is. A blade of grass, a stubbed toe, a weathered stone in the shape of a heart. One of the things we chant in our evening gatha is that the dharmas are everywhere—and so it is with gifts: Chances to awaken surround us at all times, offering themselves up. How will we receive them?

We’ve been given some doozies as of late. I wager not many of us were asking the universe for a Trump presidency with a side of Freedom Fries, but that’s of course what we were given. How do we see this as a gift? Is it even possible? And even if we can’t see it as a gift, can we receive it as one?

November 2024

Oh, dear Sangha. It’s always seemed to me that one of the great tenets of Zen is acceptance—just completely and utterly accepting life exactly as it—but it occurred to me just recently what a crushingly heartbreaking ask that is. Accept life as it is, with all its deep, deep suffering? With all that old age, sickness, and death? With the war and the horror and all the infinite innocent creatures torn from this world for no good reason? Oh, it’s a pretty phrase, I guess, accepting life as it is, but the true meaning of it—accepting everything—I don’t know how you can shoulder that burden and not be crushed. Today, I’m feeling pretty crushed by it myself.

It would be too easy, from this point, to slip into nihilism. I mean, if the world is fucked, what’s the point? (Of course, let’s not forget that accepting everything also means embracing all the good, too—all the beauty, and kindness, and love—though this can also be a strangely heartbreaking ask.) Either way, the serenity prayer above, and Zen itself, offers some hope—or if not exactly hope, than at least a path, a direction, a choice: action. The courage to do, and, with all our heart, change what we can. Of course, it takes wisdom to know what can be changed, and what cannot—and I think I’m struggling today with the fact that no matter what I do, this world will still be filled with suffering—I cannot change that fact. No matter what I do, old age, sickness, and death will persist. But perhaps it is only from a place of truly realizing this, and accepting it, that we can finally and freely and truly act.

October 2024

For a while there, it seemed like summer would last forever. The days were golden and long and warm, the trees green and full, the sky that endless, infinite blue—and you could sort of pretend like life was like that, too: infinite, never-gonna-end. Then, just a few days ago, my wife plucked a single, perfect leaf from the pavement—a sudden blaze of orange and red and yellow—and showed it to me. “Look,” she said.

Our Zen practice asks us to look, too—and to look more often and more closely than we might like. It’s funny, glancing through our Village Zendo calendar below, how much of our practice relates to great matter of death—most obviously, the upcoming Life and Death workshop and the ongoing Grace and Grit Support Group on aging. One might almost assume we were a morose group, we Zen practitioners, bent on the dark side of things, a grim and gloomy lot. (Of course, the opposite is true, and as Jisei and Jimon remind us in their reflection below, these workshops face the gravest of these matters not just with grace and grit but “with as much humor and kindness as we can muster.”)

September 2024

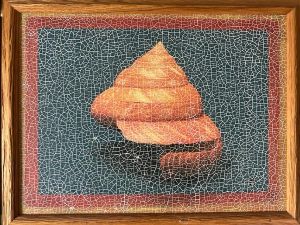

“Discover the perfection of imperfection,” was my mom’s artistic motto. She came up with it during one of her manic phases, when everywhere she looked, especially in nature, she saw immense, devastating beauty—cracked seashells, warped driftwood, bedraggled birds’ nests. She gathered these things, arranged them together, photographed them, painted over the photographs, framed the results. It was hard for me at the time to appreciate the wabi-sabi beauty of it all—mostly because my mom was acting like such a crazy person—but her creations were indeed beautiful, and the imperfections in them were often the most beautiful part. Looking back, I wish I’d been more able to appreciate my poor mom’s imperfections, too—give the lady a break—but I was young and embarrassed and yearned for someone more grounded.

Anyway, it occurs to me that in a certain sense, this is what we are doing in our Zen practice, too: seeking to discover the perfection of imperfection. Most obviously, perhaps, we do this in Zen arts. In Ikebana, for instance, which Fusho Sensei will be guiding us in later this month in the Path of Expression class, evenness and symmetry are frowned upon, and the dense, perfectly rounded bouquet of wedding roses is to be avoided at all costs. Instead, the number of flowers is always odd, stems jut off at unusual angles, and a sense of emptiness is cultivated—enough space, as Fusho once told me, for a butterfly to be able to flit in and around the arrangement with ease.

July 2024

The coming of July 4 has got me thinking about the “pursuit of Happiness,” which apparently is our God-given right as Americans. And let’s not forget Life and Liberty, either, except those the Declaration of Independence guarantees us without qualification—happiness, not so much. We tend to forget this, or misinterpret the meaning of the phrase, thinking somehow that happiness, too, is an inalienable right, when actually all we’re really entitled to is its pursuit—which could be the same thing but so often isn’t.

It’s such an American energy—this kind of a pursuit—we love chasing things (especially ethereal things like happiness that resist being found). Actually, maybe it’s not so much an American energy as it is a human energy—or perhaps, even broader, a life energy. Pursuit belongs to all forms of existence, after all. Food, water, warmth, love. All life must chase these things to persist. One might even say that the energy of the chase is life. To be after something is to be alive.

June 2024

Outside in the late-May sunshine, it is snowing. Great downy flakes are blowing about in the wind—a summer storm of fluff and seed. “Look, Ollie!” I tell my son. “It’s snowing!” “Get out of here, Daddy,” he responds.

I appreciate how in Zen, and in life, there are no real rules. It can snow in June, up can be down, a whole buffalo can pass through a window (well, except for its tail). The answer to almost everything is yes and no.

Language tries to pin things down, but Zen—and life—resists this attempt. Words fail. And yet the very act of expression—whether through a poem, or the arrangement of a few simple flowers—nevertheless embodies the Great Way itself. Words may never capture the entire truth, but in reaching for it, they sing, and that song is what life is all about.

May 2024

Imagine an existence where nothing changed. An amorphous, undifferentiated blob. Gray, uniform. No movement, no space to move, no space to breathe. No breath. Just this purgatorial between—going nowhere, on and on, forever and ever the same.

Now, perceive this existence we’ve been blessed with: This beautiful, heartbreaking world of constant flux and shift. In the front yard, a weeping cherry tree sheds its blossoms, and they are scattered to the winds. Infants are thrust, screaming, from darkness into blinding light. Beloved dogs grow old and die. One minute, the heart is pierced with great joy; the next, with great sorrow. All around us, there is space—space to breathe, to grow, to move—and everything delights in this opportunity: stirring, shifting, dancing. Atoms vibrate, birds flitter from tree to shimmering tree, the clouds rush across the sky. People come, and people go. And the color, what color!

April 2024

I’ve always wrestled with the Buddhist notions of interdependence and emptiness. As far as I understand it, the fact that everything depends on everything else—that no single thing exists in and of itself (and apart from everything else)—is what ensures that no solid, abiding, individual self exists. Or, to put it another way, because everything leans on everything else, emptiness pervades the universe. Out of relationship: emptiness.

And yet—out of relationship, what fullness! What life! Out of relationship, flower, moon, mountain, heart. Out of relationship, a helping hand, a warm hug, a kiss. Out of relationship, Sangha! Yes, who could imagine that out of emptiness, this heartbreakingly beautiful tenderness, this love, this support—and yet as Shuso Hossen so wonderfully demonstrates, this is what we belong to: this is who we are, and what life is. Or, as Jyākuen wrote in a recent email, “We are all part of the most Amazing Community—Sangha, Sangha . . . SANGHA.”

March 2024

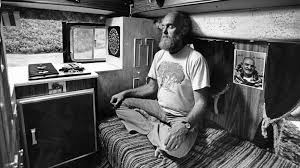

I stole the above Ram Dass quote from the wonderful conversation between Ryusho and Tendo on the joys and hardships of parenting (see below for the whole interview—it’s a really good one). One of the things that stuck with me from their intimate discussion—besides the great truth that family is a relentless place of practice—is how valuable Sangha is in letting us know that we are not alone. As Tendo so eloquently puts it, “The idea, ‘There’s something wrong with me,’ shifted to, ‘Well, this is what people experience.’”

Me, I’ve always been a bit of a loner. Even today, despite (and perhaps directly related to) the demanding relationship of spouse and kid, I imagine an escape to the mountains of Tibet—some solo hermitage, a cozy cave perhaps, where I could have the space and time and solitude to finally figure it all out, become enlightened, and live happily ever after. Of course, the whole point of the Ram Dass quote is exactly how insubstantial that kind of enlightenment is—who cares if you’re one with the universe when you’re on some distant mountain? (Especially if when you come down from the mountains and rejoin your family, you immediately turn back into an asshole.) The enlightened way has to be practiced in the everyday—in relationship—or it probably doesn’t mean much.

February 2024

I’ve been noticing my nonsense a bit more as of late. (Not that I’ve been able to do much about it, but I guess noticing is a start.) For instance, my moods around the house with my wife and kid. I see myself clinging to momentary misery with such determination and loyalty, when really, what actually has happened that’s so awful: Undone dishes? An unwalked dog?

Of course, there’s a perverse kind of satisfaction in feeling like the world is out to get you—it buoys up the self. It’s you against an unjust universe—a real underdog story. Massively indulgent, you wallow contentedly in self-righteous indignation. Who knew there could be so much pleasure in misery?

The real absurdity of this behavior is how much real misery there is out there in the world. I mean, there’s more than enough suffering already—do I really have to invent more? Apparently, yes, I do. I’m not sure, but I suspect that, as with most human issues, this may be a fear thing. Because just as a dedication to misery can solidify the self, so can true joy dissolve it. And as much as we Zen students profess to want to forget the self, I know from personal experience that often that’s sort of the last thing I want. Instead, I’ll do anything and everything in my power to keep myself from disappearing.